The interview

|

The interview |

|

| Back to Faq |

|

The following is an interview granted by Fred Freiberger, Space: 1999's second season co-producer, to the magazine StarLog and published in November 1980. It's also possible to read my translation into Italian.

|

|

|

An interview with Fred Freiberger

by Mike Clark & Bill Cotter

StarLog 40 - November 1980

SL: Tell us about your work on Space: 1999. How did

it come about?

FF: We had meetings with Abe

Mandell and Gerry Anderson, and I went over to England for three weeks to discuss the

feasibility of continuing the series. We had to generate enough enthusiasm and confidence

in Mandell and Lew Grade's organization to make it a viable series the second year. Gerry

and I sold them on continuing the series based on this new character Maya. One of the

reasons I was able to come up with Maya was part of my science-fiction background. I

worked three years with Hanna-Barbara on their Saturday morning shows. Working in kid's

television sparks your imagination; you can do some wild things.

FF: We had meetings with Abe

Mandell and Gerry Anderson, and I went over to England for three weeks to discuss the

feasibility of continuing the series. We had to generate enough enthusiasm and confidence

in Mandell and Lew Grade's organization to make it a viable series the second year. Gerry

and I sold them on continuing the series based on this new character Maya. One of the

reasons I was able to come up with Maya was part of my science-fiction background. I

worked three years with Hanna-Barbara on their Saturday morning shows. Working in kid's

television sparks your imagination; you can do some wild things.

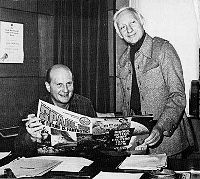

(Photo: Fred Freiberger is on the right, near to Gerry Anderson)

SL: Some viewers have expressed the thought that Maya was a

"token alien."

FF: Nobody was thinking "token" anything. Star Trek did a lot of morality

plays—that wasn't my concern here. I was there to get a show back on the air again

that would get ratings and would be entertaining in the American sense.

SL: Was Catherine Schell your original choice for the Maya

part?

FF: No. We went after Teresa Graves to be Maya. We wanted her but we heard that she was

deep into religion and had gone into retreat somewhere…had left acting. The original

Maya was to have been a black girl. We did test a lot of black girls in England. We would

have loved Teresa Graves, but we couldn't get her. Abe Mandell recommended Catherine

Schell: we looked at that Pink Panther film she was in and were quite impressed. The

character of Maya was one tough concept to sell to the British writers, but for some

reason, easier to sell to the Americans. I knew that science-fiction fans would accept

this character if we did it right.

SL: Were you considering major cast changes for Year II?

FF: When I went over to England, Barry Morse played a scientist in the series. I said,

"Gerry, if you're going to have anybody as a professor, he should be a young kid with

a beard. Do something different. Another problem with the show is that you can't have

people standing around and talking and being philosophical with these long

speeches...nobody will hold still for it. Let's do some switches on the characters. There

was a big question of the budget. We made several trans-Atlantic calls to Martin Landau

and Barbara Bain...would they take a salary cut? They wouldn't take a cut. People assume

when you're making an offer that you're lying and that they're in the driver's seat. This

show was on the edge for weeks...it looked like we were finished. I stayed an extra week,

and then it looked like 1999 had a life when I came up with Maya.

SL: What happened to Barry Morse?

FF: Barry Morse's agent came in demanding a big raise. Gerry made him a counter-offer.

Morse's agent made a bad tactical error which was sheer insanity for an agent. He said,

"No, If it's not going to be that amount, we're finished. We're out." So

immediately Gerry said, "Okay, you're out." What an agent should say is,

"He's out...except...I'll have to check with him." We had big discussions about

how to explain the disappearance of Professor Bergman, that he had a disease or something,

and they asked us to take it out. Barry Morse is an excellent actor, but I felt his part

was all wrong.

SL: How did the changes in Barbara Bain's character come

about?

FF: When I had spoken on the phone to Barbara, whom I had never met, she was charming and

delightful. I said, "Barbara, why don't you do that in the series?" Her training

at the Actor's Studio in New York told her: Be economical, which was all wrong for this

type of show. I tried to give her more to do. I tried to give her some sense of humor

because she's a natural in social situations. She's sharp. She knows story and character

very well. Marty [Landau] was a delight, an excellent actor and fun on the set...he tells

beautiful stories. I have great respect for Marty and Barbara, but I think science-fiction

should have young faces.

SL: Why was the character of Sandra seen sporadically in Year

II?

FF: Zienia Merton, who played Sandra, wanted more to do and was offered a job somewhere

else, so we lent her out for several episodes and brought in the character of Yasko,

director Ray Austin's wife. We kept Nick Tate. Nick was very nervous when Tony Anholt came

in, and always had his agent on us. We tried to use everybody. The New York office told us

to drop Tate; I said no, it would be wrong.

SL: Tell us about other changes for 1999's second year.

FF: We cut down the whole vast control center...cut down the loss of Eagles. I felt if we

were going to use violence of that sort...use it meaningfully. The English, when they did

these shows, desperately wanted to reach the American market, since that's where all the

money is. And they would interpret "action" literally as action—shooting

down a million Eagles...blasting away and doing wild physical thing...instead of dramatic

action...conflict. These are tough concepts for them to be able to understand and accept.

SL: Overall, what were the problems with 1999, as you saw

them?

FF: They were doing the show as an English show, where there was no story, with the people

standing around and talking. They had good concepts, they have wonderful characters, but

they kept talking about the same thing and there was no plot development. 1999 opened

extremely well in the United Sates and then went right down the tubes. There was nobody

you cared about in the show. Nobody at all. The people themselves didn't care about each

other. I did a whole thing where I at least had a scene where somebody said, "My God!

He's gonna be hurt! Is he dead? Is he alive?" They just didn't do that. In the first

show I did, I stressed action as well as character development, along with strong story

content, to prove that 1999 could stand up to the American concept of what an

action-adventure show should be. Abe Mandell was pretty nervous, but we were well received

by the reviewers. A few of them said, "Gee, the show is vastly improved, but it's too

late to save it."

SL: Why were there no American guest stars on 1999?

FF: British union rules. Marty and Barbara are both Americans. Even when I came over, they

had to get special dispensation for me. For there to be an American guest star, I think

there would have been big problems with the unions.

SL: Were you able to use any American writers?

FF: I was allowed six American writers, but in answer to your question, no. I didn't want

to work from 3,000 miles away.

SL: Were you getting acceptable scripts from the British

writers?

FF: At the beginning of the season you're very fussy about scripts, but as the year goes

on and you reach 18 or 20 episodes, the stuff that looked terrible to you at the beginning

starts to look like pure solid gold. I would explain things to the English writers very

carefully—because I was sensitive to their feelings—how the script should be

written for the American viewer. They were very cooperative, very creative. There were

several English plot structures I came across that I felt weren't right for us (mostly in

terms of character), for an action-type series. As a television series producer, if you do

24 one-hour episodes, and end up with four clinkers, I think you've got one hell of an

average. I wrote three scripts under the table, using the pseudonym "Charles

Woodgrove." My stories were "Space Warp," "The Rules of Luton"

and "The Beta Cloud."

SL: Coincidentally, we wanted to ask why Maya's metamorph

abilities were changed in "The Rules of Luton" script. In other stories, Maya

could change from one form to another without reverting back to her normal self. In

"Luton" she is changed into a bird, captured and held prisoner in a small wire

cage, unable to change into something smaller and escape. Why

was this done?

FF: In this case I'll just have to claim "writer's license."

SL: "Beta Cloud" seemed to be a rehash of the

standard B.E.M. (Bug-Eyed Monster) type of story.

FF: What I did was try to get into the situation. How do you defeat the undefeatable? What

intrigued me is that the Alphans could not seem to defeat this creature. Finally Maya

becomes a bee and enters the creatures ear, discovering it to be a machine. David Prowse,

who of course is now famous as Darth Vader, was in the costume.

SL: How many days on the average were you given to shoot an

episode of 1999?

FF: Ten days, not including our special-effects stage; nine hours of shooting a day. In

the U.S., you begin work at 8 a.m. and pull the plug at 6 p.m. In England, its 9 a.m. to 6

p.m. They shoot more in the U.S., too, because there's overtime built into the budget.

SL: In a press release sent to STARLOG, ITC says the second

season budget for 1999 was upped from the $6 million for Year 1 to $7.2 million for Year

II. This would break down to $300,000 per episode. Was that your typical working budget?

FF: That's nonsense! We brought them in for $185,000 per episode, which got them fantastic

production values. That's $300,000 figure is probably just for publicity. In England, at

that time (1976), the pound dropped to $1.80, so they got enormous revenue in terms of

dollars. The 1999 budget was predicated originally on pounds. When the pound dropped to

$1.80, for the dollars they got in domestic sales here, they got that many more pounds in

England. So, in essence, that budget leaped way up. The studio had legitimate costs of

about 25 percent. No way can you get a show in America for $200,000. The fringe benefits

alone amount to one third. A second assistant director in America gets $900 a week! We did

a black panther sequence on 1999 (in "The Exiles")...Catherine Schell made a

leap and transformed into this panther...in mid-air. We spent the whole day and it cost us

$5,000. In America it would have cost us $50,000!

SL: Is it still a good idea to do a series in England?

FF: I think so. I still think you can get, probably for two thirds of the cost here, the

type of production values necessary. The facilities are great, and so are the people.

SL: Had Space: 1999 been renewed for another season, whatchanges would you foresee?

FF: Well, I don't know if I'd make any changes. I think I injected a lot of humor,

especially between Tony and Catherine. As for Martin and Barbara, I think I beat the bad

relationships. I think if they would have the budget for not only American guest stars,

but if they could have really paid for high-class English actors, they would have had a

hell of a lot better acting. But, in terms of changes, I think that American guest stars

would be appealing for the American audience.

SL: Could you give our readers an idea of what's involved in

writing for a television series?

FF: Using the Harlan Ellison Star Trek script as an example...Roddenberry and Gene Coon

rewrote his "City on the Edge of Forever" and Ellison submitted his first draft

to the Writer's Guild awards, and it got the award. Now, that doesn't mean that the staff

people were wrong in what they wanted to do, or that he was right. This is the nature of

this business. If people come in to produce a show...Gene Roddenberry and Gene Coon or

whoever, that show has to be shaped in terms of what they think. There are over 1,200

active writers in the Writer's Guild. Writers have fragile egos. They come in and submit

something. You generally know your show better. You change that show; you rewrite that

show. You suggest what they do. You make suggestions. The professional writer is one who

has been in the business and knows what it is. No writer likes to have what he's done

changed. Some of them will accept the fact that some good suggestions are made and will

follow the guidance of the people who are running the show. The writer comes to the

producer and tells him the idea. They get the assignment. All are cut-off assignments, cut

off after story. They then come in with the story and discuss it. They adjust. At no time

does a writer have to, if he's got such integrity, and I do not say that disparagingly,

accept the change. All he has to do is leave and say, "Just pay me for my money for

that story and I'm finished." They don't have to go on with it after that. The people

who are running a show have to run that show. They can't let 22 different writers come in

and determine how the show should go. You've got to shape it, rightly or wrongly, ratings

and otherwise. The average writer that I know, if he's been around, he gets 50 percent up

on the screen. There isn't too much joy in the actual writing. The term "hack"

has a stigma attached to it, but it shouldn't, because its much tougher to hack out a job

for a format show than to write an anthology show, where you have no restrictions. But if

you're "hacking" out a job on Ben Casey or Star Trek, you've got to handle their

characters. You've got to shoehorn your story into a situation where these characters can

come in where they probably don't even belong. You're stretching the story and doing

things to get these people into that show. And it's very tough. You have to be a real

craftsman. But if you hack out a job for one of these shows, you're doing pretty damn

good. And they would always pay more money for an anthology show than for an episodic

show, and we couldn't understand why, because it was so easy to do an anthology show as

opposed to the other. Integrity's a wonderful thing when you can afford it. I have no

great admiration for the guy who wouldn't work in television or wouldn't work in a show

and chose to stay in a garret and starve to death. I don't want to live that way, but I

admire and applaud his right to do that, if that's what he wants.

|

|